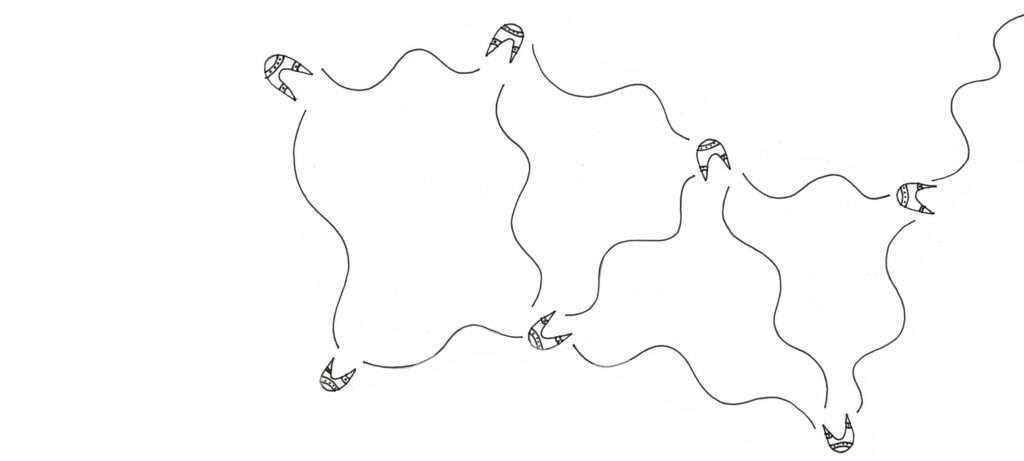

Yerlada is the Mirning word for hard shellfish and is the original name of the area. The hard shellfish is plentiful around this seacoast Country, all the way along to the Djalyingadri, whale tail.

This area holds one of our Mirning stories of sea change times, when the seal, who we call balgarda in our Mirning language, and the wombat, who have three names, wadu, wogea and wengel, the last being the seacoast wombat. The seal and the wombat were brothers and once mining, Mirning men. They went to the water at the time that they were mining and Creation beings. Balgarda went to the water and tried to see how deep it was and tried to swim, though sank. So, his brother gave him thagaloo, small wooden scoops that are used for collecting water. Balgarda put them on either side, left and right, and used them to swim. Then Balgarda gave his brother, Wardu, sticks, so they became biddy, claws, so that he could dig his holes in the ground and live and make it his home. So Wardu made his home as a wombat on the coast near his brother Balgarda, who made his home in the nearby sea and land.

Further Stories and Histories: Early Encounters

Friendly Meeting with the Dutch

The early records of the significant numbers of whalers and sealers in the Great Australian Bight reflect the contact between the Europeans (and Americans) and the Mirning people in the early 1800’s.

This was not the first meeting with non-indigenous people, as the Mirning had met the Dutch in 1627. Oral histories of that meeting under Goonminyerra, friendly laws and customs continue. Provisions of water and food were provided to the crew, who were in dire need and then sailed on safely to Batavia.

26 January 1627 Goonminyerra, friendly relations between the Mirning and the Dutch were recorded in the Fowlers Bay area. Please visit the webpage for further background on the 1627 Encounter.

Trauma of Sealers and Whalers

In 1925, Thomas Dunbabin reflected on the early colonial history of Australia and orientation to the sea in the book, Whalers, Sealers and Buccaneers. While this record is from 1925, this draws extensively from early Australian records, providing insights into pre-1825: By 1813, when white men first crossed the Blue Mountains, the great days of the sealing trade had not only come but had almost gone. Long before that the sealers in their tiny schooners or in open boats, had found their way to every rock and island in Bass Strait, round the coasts of Tasmania, and along the southern shores of Australia as far as the islands of the Great Australian Bight. p 1.

The meetings with the sealers and whalers were in stark contrast to the friendly encounter with the Dutch. When John Edward Eyre travelled through our Country in 1840, much of the sealing had been and gone and there was a fleet of whaling ships off our coast. When Eyre happened upon a group of our women and children at Fowlers Bay he noted: They were much afraid and ran away on seeing me, leaving their food upon the embers.. These few women were the first we had seen for some time, as the men appeared to keep them studiously out of our way, and it struck me that this might be in consequence of the conduct of the whalers or sealers with whom they might have come in contact on the coast.

Mirning oral history of the whalers is also recorded in an episode of Message Stick, Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2006 with Mirning Elders Aunty Margaret Lawrie (deceased), Aunty Iris Burgoyne (deceased) and Uncle Bunna Lawrie.

Margaret Lawrie: Then came the whaling. Furthermore, our special relationship with the whale was severely compromised with the introduction of whaling in our coastal waters.

Iris Burgoyne: The Mirning people just got right away from it. ‘Cause they couldn’t stand to see the whales getting killed and speared and things like that.

Bunna Lawrie: It’s like watching your own children being killed. Part of the family. It was horrible.

Margaret Lawrie: Over the last 300 years, millions of these magnificent beings have been killed. And well before the world’s petrochemical dependence – it was with the oil and blubber of our totemic sacred animals that the 19th Century’s industrial revolution was built. As the whale’s populations came close to extinction, according to the government of South Australia, so did ours.

There were some who came and were respectful, such as R.T. Maurice. In friendship, he came to know family and some of our ways. He appears to have understood how our isolation between the arid Nullarbor to the north and seas to the south made for a unique culture. In 1900 he wrote “this tribe is worthy of a book – language, morals & history being different to any I have ever come across.”

Displacement

We will not write of the ongoing hurt and harm caused by the inland desert people, who came onto our Country after colonisation. However, we cannot ignore it, nor those who have declared us extinct. This may have been fed by references to ‘extinct’ overlooking that the few remaining Yerkala Mirning were simply not easy to find or observe. In 1931 A.P. Elkin, an anthropologist, travelled from Ooldea to Port Augusta and passed through Fowlers Bay. He noted the southernly movement of the inland desert peoples and, having not met any Mirning people, he declared that: The Wanbiri-speaking tribe, referred to by Howitt as the Yerkla-mining … is now extinct … once [inland] natives have reached the East-West Line, or formerly, the coast, they are very loath to return north. Elkin, A.P. (1931) The Social Organization of South Australian Tribes p 62. (Wanbiri is wanyiri, our small native ngoora, grape.)

The name Yerlada was corrupted into Yalata for a pastoral station. In turn, the Yalata Mission was founded in 1951 at Tallowan Well, as the water had become scarce at Ooldea Mission. Many inland desert people were displaced onto our coastal Country. There are many stories of their discontent at having to live on our ‘grey-earth’ Nullarbor Country, though who asks what this has meant for us?